I have been encountering quite a few engaging perspectives since the circulation of my post on 'The OECS Buildings Codes vs Hurricane Irma". Recently, I was tagged in a post from a Chevening alumna from The Bahamas, querying my feedback on a blog entry by a Bahamian author. The title of the entry was "Irma: A Meditation on Hurricanes and the Bahamas". In reading the post, it was quite an interesting opinionated piece, and I decided to post my feedback within my own blog. My perspective is, as follows:

Well, I've never been to The Bahamas so I won't be able to definitively endorse or refute what's suggested within the post.

It's an interesting take on hurricane resistivity. The author did capture the barometric pressure contributing to how destructive a hurricane can be, but an additional element to be considered is the speed that the hurricane is moving. Sluggish movement means that the storm has a longer time on the ground. Longer time on the ground means that each building is taking a beating from the force of the winds over a longer period of time. Durability and endurance then become key factors in a building's resistivity.

Some valid points are within the post. I'm curious about the "reinforced poured concrete". If it's what I'm thinking it is, it sounds like a beneficial construction method to consider. However, I'm actually more curious about the reinforcement used (sizes and intervals - since that's what increases the integrity of the structure). However, many of the structures constructed of reinforced concrete block walls in the islands that were hit by Irma seem to still be standing, so I'm not sure if the block wall construction is under major scrutiny at the moment. That being said, I'm most curious about the roof construction, since that's the most vulnerable element in a building when enduring storm-force winds. If there are any new technologies introduced to secure roofs better (that won't excessively hurt the average person's pocket) then I'm sure they'd be welcomed in the wider region. The wall construction would really play a bigger part when it's impacted by the new roof construction techniques (whether the walls, beams, or columns would need additional reinforcement, etc).

On one hand I understand the perspective about The Bahamas not being mountainous and therefore tends to avoid land slippage caused by heavy rains in a storm, but the author did mention that the hilly topography of an island tends to reduce the intensity of the storm when it passes over. The other thing to note is that quite often hills offer protection to structures in lower lying areas from hurricane winds (flatter areas tend to be more exposed). However, alternatively, there's also the concept of the hills sometimes creating wind tunnels if they're a bit close together - but I digress.

Some of the design elements mentioned are a bit typical of the older structures in the region that were built during colonial times. The raised foundations in flood prone areas are a common feature in a lot of the islands. For example, the entire historic district in Roseau, Dominica has buildings that are raised a few feet off the ground. The transom window (above doors for cross-ventilation) is also typical in many of the antiquated structures from that era. It's also used to allow hot air to rise and escape at that level.

The author made a statement towards the end of this post that has spurned my curiosity a bit: "that we should study and standardize our building techniques—all of them, from the working in wood to our facility with concrete". Do you by chance know if The Bahamas has an approved Building Code? I'd be interested in taking a peep at it if you do. That would be a starting point in supporting the author's perspective.

Nicolette Bethel's Blog Entry, can be found here:

https://nicobethelblogworld.wordpress.com/2017/09/09/irma-a-meditation-on-hurricanes-and-the-bahamas/

Thursday, 14 September 2017

Wednesday, 13 September 2017

Barbuda for Barbudans

Today I came across an article that was published in the Jamaica Observer media house that was entitled 'Barbuda 2.0: Rebuild Devastated Island into a Modern Tourist City'.

While it may've been written with the best intentions in mind, I personally believe that we must first determine what the people of Barbuda (as a micro community) - and by extension the nationals of the entire twin-island state (as a macro entity) really want. I believe that the regional or international community projecting our economic ideals on a ravaged nation is a bit inconsiderate and inappropriate. I'm not opposed to developing Barbuda into an advanced entity, but I am hesitant in suggesting that it should be a "Modern Tourist City".

In post-volcanic Montserrat, there has been a considerable amount of contention in the notion of developing the proposed new, capital city of Little Bay into a tourism-centre. Local residents, diaspora, expats, and visitors all have varying opinions on what the island should be, and should evolve into. The concept of competing with other islands who's tourism sectors are more established, is not an appealing thought for some. Meanwhile, others welcome the idea of expanding Montserrat's reach into the global market. Many still believe that Montserrat should target niche areas of tourism - focusing on low numbers, but high spenders. Others however, still hold firm that we should be increasing our visitor arrivals on an annual basis.

As I mentioned before, as an Architect who's interest is in development, I would eagerly support the opportunity to improve the Barbudan environment. However, we must be sensitive to the inhabitants and ensure that when this island is developed it still has the Barbudan cultural identity EMBEDDED within the domain. A "modern tourism city" only creates a replica of so many different towns within the region. It is at this critical point, when the impact of globalization should be carefully considered.

Each island within the Caribbean has it's own charm and uniquely enticing environment for tourists. Barbuda's enthrall may very well be the very aspect that some developers could be seeking to change.

"Luxury resorts" and high-end commercial environments tend to encourage a divide between the 'haves and have-nots' in a community - potentially impacting crime rates, and motivating gentrification. As professionals within the built environment, it is our responsibility to ensure that when we develop, it is not merely because we have been placed an "almost virginal" canvas before us - but instead, to shape spaces and create communities that are for the people.

This is our social responsibility.

The article from the Jamaica Observer, is below:

http://www.jamaicaobserver.com/editorial/barbuda-2-0-rebuild-devastated-island-into-a-modern-tourist-city_110643?profile=1100

Monday, 11 September 2017

Adhering to Building Codes Within the Caribbean and Further Questions

Subsequent to the passing of Hurricane Irma, I have been receiving a few questions on the building codes within the OECS, as well as on construction techniques within the region. The following were posed to me by a commenter on Facebook:

Commenter: "I saw a clip from an Antigua disaster official who indicated that Barbuda houses were not built to code. Not sure if that explains why all the roofs were gone or whether most houses were not built to withstand a cat 5 winds. It's impressive that the walls remained.

Hopefully Caribbean governments, esp. OECS countries will study the roofs that survived and determine whether the codes need updating. It seems like Hugo was the driver of [the] last major code updates.

Response: The last update of the OECS Building Code was in 2015. The problem that we're having right now is that some of the islands haven't passed it as a legal document (admittedly, including Montserrat). The islands within the Caribbean have specific windspeed thresholds related to where they're geographically located. The islands on the northern area of the chain have higher thresholds, while the ones on the lower end have lower [thresholds]. This is mainly because hurricanes tend to have trajectories that are more in the upper area of the island chain. That being said, the main issue we tend to have with our construction within the Caribbean isn't the code itself - it's actually the enforcement of the code. Some individuals choose no to submit plans for approval through the correct processes, and instead decide to build as they deem fit. Planning authorities sometimes are also influenced by the political electorate, and as such, issues sometimes slide under the table.

Commenter: "I have a few questions that I would love for you to answer:

Question 1: Will it be cost prohibitive to change the code for houses to be built to withstand cat 5 hurricanes? Although it [is] a rare occurrence, it is possible that it may become the new reality."

Answer: One issue [that the region is having] is that there are some older structures (even historical ones) that would need significant upgrading to meet the code. Of course, that would result in a conflict if they're protected under historical building regulations. Also, to retrofit some of the structures that were constructed prior to the introduction of the code would result in high costs, and a headache to attempt to retrofit. The other thing to note, is that there are different building classifications in each building code. Some categories have lower thresholds for wind speeds, while others have higher thresholds (meaning, not all building types must be designed to withstand a category 5 hurricane).

Question 2: "Are many houses in the OECS built with truss roofs? This is the first time I'm hearing that term and had to Google it. I was only familiar with the rafters."

Answer: Not many buildings (especially residential) are designed with truss roof systems. Some of the older structures do have them though. As I mentioned [previously], they can be costly, and many people tend to shy away from making grand investments in structures when the typical gable or hip roofs will do fine in areas that don't have frequent Cat 5's. In some instances, a truss roof system (alone) for a 2-bedroom unit can end up costing almost as much as an entire 2-bedroom building with the rafter roof.

Question 3: "Can you share a pic with a house with a Mansard Roof? When I Google Mansard Roof I'm seeing images of roofs I've seen on apartments in the US and I don't recall seeing those kind of roofs in the Caribbean. I'm hoping that Irma can start a dialogue regarding our building practices in the Caribbean. I know we love to boast that our houses are built from solid steel reinforced concrete and I'm thinking that we probably need to start focusing more on how our roofs are built. Thanks."

Answer: I've attached the Mansard Roof. We have a few Mansard Roofs within the Caribbean. Another name for it is the "gambrel roof". The designs would've been brought over from the French during the colonial era."

Image of a Mansard Roof is courtesy of:

http://study.com/academy/lesson/what-is-a-mansard-roof-definition-design.html

Commenter: "I saw a clip from an Antigua disaster official who indicated that Barbuda houses were not built to code. Not sure if that explains why all the roofs were gone or whether most houses were not built to withstand a cat 5 winds. It's impressive that the walls remained.

Hopefully Caribbean governments, esp. OECS countries will study the roofs that survived and determine whether the codes need updating. It seems like Hugo was the driver of [the] last major code updates.

Response: The last update of the OECS Building Code was in 2015. The problem that we're having right now is that some of the islands haven't passed it as a legal document (admittedly, including Montserrat). The islands within the Caribbean have specific windspeed thresholds related to where they're geographically located. The islands on the northern area of the chain have higher thresholds, while the ones on the lower end have lower [thresholds]. This is mainly because hurricanes tend to have trajectories that are more in the upper area of the island chain. That being said, the main issue we tend to have with our construction within the Caribbean isn't the code itself - it's actually the enforcement of the code. Some individuals choose no to submit plans for approval through the correct processes, and instead decide to build as they deem fit. Planning authorities sometimes are also influenced by the political electorate, and as such, issues sometimes slide under the table.

Commenter: "I have a few questions that I would love for you to answer:

Question 1: Will it be cost prohibitive to change the code for houses to be built to withstand cat 5 hurricanes? Although it [is] a rare occurrence, it is possible that it may become the new reality."

Answer: One issue [that the region is having] is that there are some older structures (even historical ones) that would need significant upgrading to meet the code. Of course, that would result in a conflict if they're protected under historical building regulations. Also, to retrofit some of the structures that were constructed prior to the introduction of the code would result in high costs, and a headache to attempt to retrofit. The other thing to note, is that there are different building classifications in each building code. Some categories have lower thresholds for wind speeds, while others have higher thresholds (meaning, not all building types must be designed to withstand a category 5 hurricane).

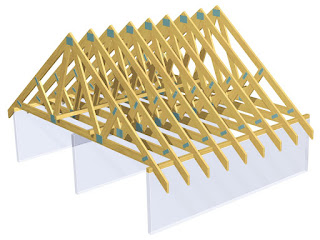

Question 2: "Are many houses in the OECS built with truss roofs? This is the first time I'm hearing that term and had to Google it. I was only familiar with the rafters."

Answer: Not many buildings (especially residential) are designed with truss roof systems. Some of the older structures do have them though. As I mentioned [previously], they can be costly, and many people tend to shy away from making grand investments in structures when the typical gable or hip roofs will do fine in areas that don't have frequent Cat 5's. In some instances, a truss roof system (alone) for a 2-bedroom unit can end up costing almost as much as an entire 2-bedroom building with the rafter roof.

Question 3: "Can you share a pic with a house with a Mansard Roof? When I Google Mansard Roof I'm seeing images of roofs I've seen on apartments in the US and I don't recall seeing those kind of roofs in the Caribbean. I'm hoping that Irma can start a dialogue regarding our building practices in the Caribbean. I know we love to boast that our houses are built from solid steel reinforced concrete and I'm thinking that we probably need to start focusing more on how our roofs are built. Thanks."

Answer: I've attached the Mansard Roof. We have a few Mansard Roofs within the Caribbean. Another name for it is the "gambrel roof". The designs would've been brought over from the French during the colonial era."

Image of a Mansard Roof is courtesy of:

http://study.com/academy/lesson/what-is-a-mansard-roof-definition-design.html

Storm Resistant Roofs In the Caribbean Hurricane Belt

Since my recent post on the OECS Building Codes vs Hurricane Irma, I have been posed with some interesting and valid questions from residents throughout the reign, on what exactly makes a building capable of resisting the impact of Category 5 Hurricanes. Someone posted an interesting query on a friend's post, and I thought I'd share my response on social media.

Question: "What type of roofs will be needed to withstand a Category 5 Hurricane besides a concrete roof?"

Answer: Many times when a building falters structurally, it's primarily at the joints/connections (especially connections between 2 or more different material types). One of the most vulnerable elements in a building during a storm is the roof (especially if it's a timber frame roof - particularly gable and hip roofs). Once the roof is tied into the frame of the building properly, the level of destruction should be considerably less. In many of the islands where Irma's eye passed through, there are still structures standing with timber roof frames intact. What has happened though, is that the roof sheeting is pulled off and the rafters are exposed.

Another issue that causes roofs to be pulled off during storm force winds, is the length of the overhangs. This however tends to be a conflict in the tropics, as we tend to like the overhangs as they offer shading to windows, verandas, etc. However, longer overhangs tend to create more surface area for wind uplift.

Another issue is the pitch of the roof. Shallower pitches = less wind resistance. Steeper the pitch, the more resistivity it has.

Also, many engineers support the idea that truss roofs tend to withstand intense weather conditions a lot better than roofs with rafters. The roof is heavier, the loads are transferred more evenly, and apparently connected a bit better to the concrete walls.. However, they're also considerably more expensive.

Plus, the use of screws opposed to nails in key areas can help a lot.

Also, the spacing/intervals between rafters, screws, etc. also help. The closer they're spaced, the more it can withstand wind resistance.

One roof type that I noticed seemed to perform well during Hurricane Irma is the Mansard Roof. I noticed a couple of them in a few photos from one of the islands (I can't recall if the photos were in the BVI or St. Maarten/St. Martin, but the images I saw had the roofs still completely intact despite the neighbouring roofs faltering). The steep pitches again seem to help with the wind resistivity.

People tend to gravitate towards the concrete slab roofs because they alleviate insecurities when it comes to hurricane resistance, but in reality, the slab roofs also come with their own demerits; maintenance can be a bit trickier than timber frame roofs, and concrete roofs tend to create 'heat boxes' - they retain the heat during the day, then release it during the night. The other thing to note is that one of the primary reasons for the incorporation of hip or gable roofs into tropical architecture is to allow the hot air to rise into the apex, and keep the lower areas of the building cooler.

Image courtesy of:

Truss Roof - http://www.diynetwork.com/how-to/rooms-and-spaces/exterior/all-about-roofs-pitches-trusses-and-framing

Question: "What type of roofs will be needed to withstand a Category 5 Hurricane besides a concrete roof?"

Answer: Many times when a building falters structurally, it's primarily at the joints/connections (especially connections between 2 or more different material types). One of the most vulnerable elements in a building during a storm is the roof (especially if it's a timber frame roof - particularly gable and hip roofs). Once the roof is tied into the frame of the building properly, the level of destruction should be considerably less. In many of the islands where Irma's eye passed through, there are still structures standing with timber roof frames intact. What has happened though, is that the roof sheeting is pulled off and the rafters are exposed.

Another issue that causes roofs to be pulled off during storm force winds, is the length of the overhangs. This however tends to be a conflict in the tropics, as we tend to like the overhangs as they offer shading to windows, verandas, etc. However, longer overhangs tend to create more surface area for wind uplift.

Another issue is the pitch of the roof. Shallower pitches = less wind resistance. Steeper the pitch, the more resistivity it has.

Also, many engineers support the idea that truss roofs tend to withstand intense weather conditions a lot better than roofs with rafters. The roof is heavier, the loads are transferred more evenly, and apparently connected a bit better to the concrete walls.. However, they're also considerably more expensive.

Plus, the use of screws opposed to nails in key areas can help a lot.

Also, the spacing/intervals between rafters, screws, etc. also help. The closer they're spaced, the more it can withstand wind resistance.

One roof type that I noticed seemed to perform well during Hurricane Irma is the Mansard Roof. I noticed a couple of them in a few photos from one of the islands (I can't recall if the photos were in the BVI or St. Maarten/St. Martin, but the images I saw had the roofs still completely intact despite the neighbouring roofs faltering). The steep pitches again seem to help with the wind resistivity.

People tend to gravitate towards the concrete slab roofs because they alleviate insecurities when it comes to hurricane resistance, but in reality, the slab roofs also come with their own demerits; maintenance can be a bit trickier than timber frame roofs, and concrete roofs tend to create 'heat boxes' - they retain the heat during the day, then release it during the night. The other thing to note is that one of the primary reasons for the incorporation of hip or gable roofs into tropical architecture is to allow the hot air to rise into the apex, and keep the lower areas of the building cooler.

Image courtesy of:

Truss Roof - http://www.diynetwork.com/how-to/rooms-and-spaces/exterior/all-about-roofs-pitches-trusses-and-framing

OECS Buildings Codes vs Hurricane Irma

A few days ago I wrote a post on social media about the Building Codes in the Eastern Caribbean vs Hurricane Irma. This post was written in anticipation for future backlash on the Codes within the islands, as unfortunately, there was a significant amount of damage throughout 7 of the islands that were impacted by the devastating Hurricane Irma. The post went viral throughout the Caribbean as a few days later, a couple of Floridians made derogatory statements about the building construction within the region. I've decided to share the post here, as a part of my blog. The links to a few of the articles on the post from different media houses, are listed below.

To be clear, the destruction left in the wake of Hurricane Irma is NOT an indictment on the construction techniques within the Eastern Caribbean. The building codes in the Eastern Caribbean dictate that buildings should be designed to take wind speeds of between 154mph - 180mph, depending on the location and category of building.

Each island that the OECS Building Code accounts for that was affected by Hurricane Irma, has buildings that can withstand storms up to the following wind speeds:

Antigua & Barbuda - 168 mph

Anguilla - 176 mph

British Virgin Islands - 180 mph

St. Kitts & Nevis - 170 mph

Montserrat - 172 mph

Irma is an anomaly of a superstorm that hit the islands at 185 mph.

To put this into perspective: the frequency of Category 5 hurricanes that make a direct hit on each of the Caribbean islands isn't on an annual basis. Cat 5's start at wind speeds of 157 mph. A hurricane that reaches land at even 160 mph tends to go down in the record books.

To put this into perspective: the frequency of Category 5 hurricanes that make a direct hit on each of the Caribbean islands isn't on an annual basis. Cat 5's start at wind speeds of 157 mph. A hurricane that reaches land at even 160 mph tends to go down in the record books.

Our construction techniques in the Caribbean region have improved considerably after 1989, when Hurricane Hugo hit the Eastern Caribbean and caused a considerably amount of damage. Hurricane straps, ties, the distance between rafters, etc. were all rethought and strengthened. Although we always welcome new and improved construction technologies, our Building Code is sound, and many of our construction techniques are superior to those in many international countries.

Links to articles on the post:

- Loop TT:

http://www.looptt.com/content/architect-responds-after-floridians-call-caribbean-houses-cardboard

- Discover Montserrat

https://discovermni.com/2017/09/11/local-architects-defense-of-oecs-building-code-gets-endorsed-by-code-author/

Photos courtesy of:

Image 1 - Steel that was once upright prior to the passing of Hurricane Irma in one of the Caribbean islands. This image shows the intensity of the Category 5++ hurricane. Image is courtesy of Dr. Lavida Thomas-Richardson.

Image 2 - Destroyed buildings in the island of Barbuda after Hurricane Irma. Image was circulated on social media subsequent to the passing of Hurricane Irma. (I do not own the rights to this image).

Image 3 - Destroyed Princess Juliana Airport in the island of St. Maarten/St. Martin after Hurricane Irma. Image was circulated on social media subsequent to the passing of Hurricane Irma. (I do not own the rights to this image).

To be clear, the destruction left in the wake of Hurricane Irma is NOT an indictment on the construction techniques within the Eastern Caribbean. The building codes in the Eastern Caribbean dictate that buildings should be designed to take wind speeds of between 154mph - 180mph, depending on the location and category of building.

Each island that the OECS Building Code accounts for that was affected by Hurricane Irma, has buildings that can withstand storms up to the following wind speeds:

Antigua & Barbuda - 168 mph

Anguilla - 176 mph

British Virgin Islands - 180 mph

St. Kitts & Nevis - 170 mph

Montserrat - 172 mph

Irma is an anomaly of a superstorm that hit the islands at 185 mph.

To put this into perspective: the frequency of Category 5 hurricanes that make a direct hit on each of the Caribbean islands isn't on an annual basis. Cat 5's start at wind speeds of 157 mph. A hurricane that reaches land at even 160 mph tends to go down in the record books.

To put this into perspective: the frequency of Category 5 hurricanes that make a direct hit on each of the Caribbean islands isn't on an annual basis. Cat 5's start at wind speeds of 157 mph. A hurricane that reaches land at even 160 mph tends to go down in the record books.Our construction techniques in the Caribbean region have improved considerably after 1989, when Hurricane Hugo hit the Eastern Caribbean and caused a considerably amount of damage. Hurricane straps, ties, the distance between rafters, etc. were all rethought and strengthened. Although we always welcome new and improved construction technologies, our Building Code is sound, and many of our construction techniques are superior to those in many international countries.

Links to articles on the post:

- Loop TT:

http://www.looptt.com/content/architect-responds-after-floridians-call-caribbean-houses-cardboard

- Discover Montserrat

https://discovermni.com/2017/09/11/local-architects-defense-of-oecs-building-code-gets-endorsed-by-code-author/

Photos courtesy of:

Image 1 - Steel that was once upright prior to the passing of Hurricane Irma in one of the Caribbean islands. This image shows the intensity of the Category 5++ hurricane. Image is courtesy of Dr. Lavida Thomas-Richardson.

Image 2 - Destroyed buildings in the island of Barbuda after Hurricane Irma. Image was circulated on social media subsequent to the passing of Hurricane Irma. (I do not own the rights to this image).

Image 3 - Destroyed Princess Juliana Airport in the island of St. Maarten/St. Martin after Hurricane Irma. Image was circulated on social media subsequent to the passing of Hurricane Irma. (I do not own the rights to this image).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)